In the foothills of the Sierra Nevada in Spain’s southernmost region of Andalusia, on a plateau overlooking the city of Granada, stands the Alhambra. Meaning “The Red One” in Arabic (a direct reference to the reddish tint of the tapia, or rammed earth, used to build its outer walls), the Alhambra is widely regarded as the most astonishing monument of Moorish architecture to be found on the Iberian peninsula.

The complex covers an area of about 35 acres and consists of three main sections. The Alcazaba, or citadel, is a centrepiece of extensive fortifications on the westernmost tip of the plateau. Then there is the cluster of palaces and houses of worship built behind it. Lastly, the Generalife is a country estate located just outside of the central compound’s eastern walls.

On top of boasting one of the best-preserved palaces of the Islamic Golden Age, the site also contains several notable examples of Spanish Renaissance architecture. This wealth of history has led the Alhambra to become one of the most visited tourist attractions in all of Spain.

The Alhambra: A Brief History

The Alhambra was primarily constructed between 1238 and 1358 at the behest of Ibn al-Ahmar ˗ founder of the Nasrid dynasty and the Emirate of Granada, the last in a long succession of Islamic states that once ruled over the territories of modern-day Spain and Portugal ˗ and his descendants.

During the Nasrid era, it was a self-contained city separate from Granada and the rest of the Vega (meadow) below. The complex was equipped with a mosque, tannery, artisan workshops, and hammams (public baths), which were fed by a sophisticated water supply system. The palaces built during this era are generally considered to be the compound’s crown jewels, best known for the intricate decorations and inscriptions that adorn their inner walls.

An Era of Neglect

Following the conclusion of the Reconquista and subsequent expulsion of Boabdil ˗ the 22nd and last Nasrid ruler of Granada ˗ in 1492, the site became the court of Ferdinand II and Isabella I of Spain. Random fact: It is where Christopher Columbus received endorsement for his expedition that would lead to the “discovery” of the New World. Sadly, despite maintaining its royal status, “The Red One” would gradually be allowed to fall into disrepair under Catholic control.

Charles V had parts of the original complex destroyed with the intention of erecting a monumental palace in the Renaissance style. Construction of said palace commenced in 1527 and continued for a staggering 110 years, after which it was left uncompleted.

By the time the army of Napoleon I rode into Granada in 1810, most of the site’s dilapidated buildings were inhabited by squatters. The French troops that replaced them only caused further destruction. Upon evacuating Granada in 1812, they attempted to dynamite the Alhambra to high heaven to prevent it from being used as a fortified position. Eight towers were blown to smithereens before the remaining fuses were disabled by a Spanish soldier.

To make matters worse, an earthquake ravaged much of what had remained intact in 1821. Thankfully, a group of prominent granaínos (residents of Granada) led by architect José Contreras initiated an extensive rebuilding program that received royal endowment in 1830. José’s son and grandson would also dedicate their lives to the restoration of the site’s glory.

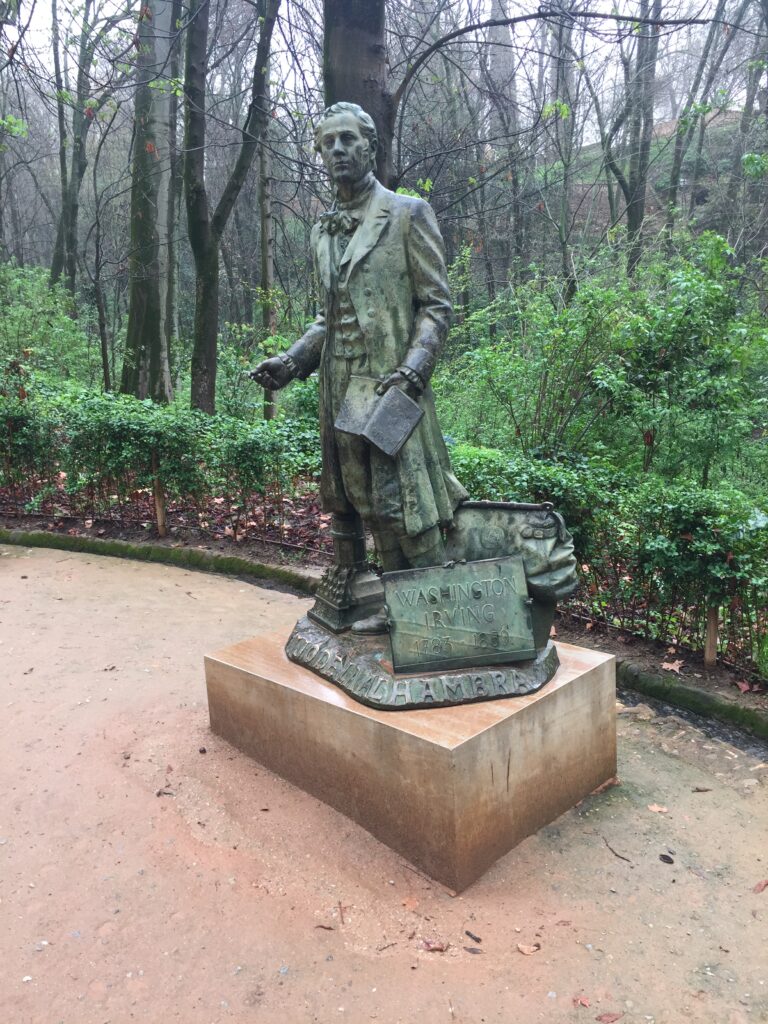

The efforts of the Contreras lineage, and all those that shared their vision, did not go unnoticed. British intellectuals and “romantic” travellers from northern Europe and the USA started showing an interest in the Alhambra too, the most influential of them being an American author by the name of Washington Irving.

The Original Tales

Best known for his short stories “Rip Van Winkle” (1819) and “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” (1820), Washington Irving was one of the first writers from the other side of the pond to earn acclaim in Europe. Of Manhattan merchant stock, Irving left for England in 1815 in an unsuccessful bid to salvage the family business and would end up travelling the old continent for the next seventeen years.

He resided in Madrid from 1826 until 1829 and, after finishing the biography of Christopher Columbus he had been working on whilst there, also spent some time in Granada to continue researching another book he had begun writing. Due to his celebrity status, Irving’s request to the then-governor of the Alhambra and the archbishop of Granada to stay on the palace grounds was permitted. This enviable experience inspired him to write “Tales of the Alhambra”, a collection of essays, short stories, and verbal sketches published in 1832.

In the Footsteps of Greatness

I started reading “Tales of the Alhambra” in March, shortly before departing on a ten day trip to Andalusia. I had never been and was determined to cover as much ground as possible. However, circumstances on the home front being as they are, there was a distinct possibility I would not be able to make the trip at all.

Therefore, with the exception of my flights, the only reservation I made in advance was to go and see “The Red One”. Bearing in mind that the place is crawling with tourists year-round, some two million in total, it seemed wise to purchase a ticket sooner rather than later. Setting that date also helped me charter the general course of my journey.

After spending two nights in Málaga, I caught a bus up to Granada. Much of the two-hour ride was spent soaking up Irving’s graceful descriptions of the place I was headed and peering out the window as we climbed and plunged through rocky hill country. It was a Tuesday afternoon and the sky was coloured an eerie shade of dark yellow. After reaching higher ground, the mist set in.

Granada was bedecked with a blanket of haze so thick that its majestic guardian up on the plateau was nowhere to be seen. Being somewhat oblivious to the local weather phenomena, I thought nothing of it. Moreover, I’d experienced smog even more impenetrable whilst living in South East Asia so I knew better than to let it hold me back.

No more than an hour after walking out of Granada’s shabby bus terminal, my search for suitable accommodation had been concluded. Since I would not be permitted to enter the Alhambra until the following day, I spent the remainder of the afternoon wandering around the awe-inspiring Albaicín (pronounced Albayzin) quarter.

The Albaicín

The oldest section of the city, this charming labyrinth of narrow cobblestone streets is lined with cármenes (Moorish-style houses) and dotted with public squares populated by citrus trees. Built against the slopes of a hill, the neighbourhood is separated from the plateau on which the Alhambra stands by the trickle that is the River Darro. Passing through the Puerta de Elvira ˗ Granada’s main access gate in the days of Moorish domination ˗ at the lowest point of the quarter, “The Red One” was still unaccounted for.

When I did finally catch a glimpse of its magnificence, at the top of a long flight of steps right up the street from Puerta de Elvira, it was love at first sight. From that moment on, the Alhambra sprung into view every time I looked up and around me. The higher I trudged, the vista became clearer. I soon gave up on taking pictures for it was impossible to capture the sense of awe I was experiencing.

A rain shower passed over and I was baffled to find that my jacket, the white Nike Air Force One’s I’d managed to keep in near-pristine condition for over two years, and the cobble stones they trod on were covered in a thin layer of brown powder comparable to wet sand. It did not make any sense but it didn’t really matter either; I was utterly spellbound by the Alhambra and it commanded my full attention.

Downtown

The next shower lingered long enough to become a nuisance and I ducked into a cervecería (pub) on the Plaza de Santa Ana, tucked between the Alhambra and the Albaicín at the point where the River Darro is diverted underground. Two jarras de cerveza (mugs of beer) and a light meal later, it had stopped raining and I was ready to do some more sightseeing.

An old friend of mine, whom we shall henceforth refer to as Tío Triana (a direct reference to his advanced maturity in combination with his surname), spent several months working on a project in Granada some years ago and had sent me a long list of recommendations on what to see and do during my short stay.

After wandering around Granada’s old Jewish quarter and other parts of the city centre for a while, I veered off the beaten tourist paths in search of Tío Triana’s favourite taperías (tapas bars). Unfortunately, one proved impossible to find – on account of it being out of business, I would later find out – while the other only opened its doors at 9 p.m., which left me with more than half an hour to kill.

It had started raining again and the exertions of the day were starting to take their toll. More importantly, I was getting a bit thirsty. As luck would have it, it did not take long for me to stumble upon Café Bar Garden, where I enjoyed my first taste of Granada’s local brew.

Cervezas Alhambra

It almost goes without saying that the beer in question was named after the city’s most recognisable landmark. Founded in 1925 by the owner of the La Moravia malthouse near Barcelona and a granaíno brewmaster, Cervezas Alhambra garnered considerable local acclaim in the decades that followed despite being a small-scale operation with no more than twenty employees.

That all changed in 1954 when S. A. Damm, a Barcelona-based brewery, became major shareholder in La Moravia and invested heavily in the upgrade of its production facilities. In 1979, when Damm decided to sell its shares in Cervezas Alhambra, the latter had around four hundred people on its payroll.

Cruzcampo, another brewery of Andalusian origin based in the region’s capital of Seville, became a minority shareholder in the wake of Damm’s abdication. However, the steep upward trend of the previous quarter century could not be maintained. By 1995 Cervezas Alhambra had accumulated sizeable debts and was forced to sell 99% of its shares to an external group at a low price after Cruzcampo had abandoned ship.

Thankfully for us all, a remarkable resurgence sparked by an impressive display of support from the local community took place and the company was turning profit again the following year. During that period, while the overall Spanish beer market shrunk by 3%, sales of Cervezas Alhambra went up by 27%.

Alhambra Reserva 1925

The good times kept on rolling with the introduction of the Alhambra Reserva 1925 in 1998, a scrumptiously rich reinterpretation of the Bohemian-style pilsener. The brew proved a real hit with self-proclaimed beer connoisseurs near and far and went on to win the title of World’s Best Standard Premium Lager at the 2009 World Beer Awards. The Reserva’s popularity can be partially attributed to its elegant presentation, being sold in a label-less green bottle similar to those that the brewery used for its inaugural batch in 1925.

Its success enabled, to some extent, Cervezas Alhambra to take over the Andalusian Beer Company in 1999. Best known for Mezquita, a red abbey beer dedicated to the city of Córdoba’s most famous monument, the acquisition increased overall production capacity by 60,000 cans per hour and Cervezas Alhambra became the region’s largest brewer.

While things were certainly going well for Cervezas Alhambra around the turn of the century, an interesting and potentially damaging development was taking place behind the scenes. The company was sued by Heineken in 2000 over the rights to the Aguila Negra brand, a David versus Goliath type of scenario in which the heavyweight plaintiff’s case was built on the claim that Alhambra’s Aguila Negra was illegally competing with its own El Aguila brand.

Poetic Justice

Heineken called for the brand rights to be taken away as Aguila Negra had not been produced nor sold since Cervezas Alhambra had acquired these rights in 1997. Cervezas Alhambra responded by filing a counter-suit against Heineken España’s top two executives, claiming they had hired a private detective to prove Aguila Negra was no longer being produced and that this constituted industrial espionage.

In their own version of events, the detective had illegally entered one of the company’s breweries in Córdoba with the intention of obtaining confidential information but the case was dismissed when it became clear that he had been invited onto the premises by posing as a beer expert.

In turn, the information obtained was deemed insufficient to justify Heineken’s claim. Aguila Negra and El Aguila had co-existed for many years before the former was declared bankrupt in 1997 and the fact that the brand was no longer being sold actually supported Cervezas Alhambra’s case. Hence, in 2002 the Court of Granada ruled in favour of its fellow granaínos.

Several years down the line, after the dust had settled, Cervezas Alhambra was bought by the Mahou – San Miguel group for a tidy sum of €200 million; quite the turnaround considering the company’s sorry state ten years prior.

Tasting Sessions

From what I can recall, Café Bar Garden did not serve any of the aforementioned brews. Then again, I was unaware of their existence at the time so I could very well have failed to notice. That night my thirst was quenched with two jarras of Alhambra Lager Singular (Premium Lager), a smooth yet full-bodied potion with soft fruity and floral notes accompanied by an infusion of well-balanced bitterness. A solid effort, if you ask me. Nothing that warrants superlatives, but of a distinctly higher quality than the Cruzcampo I had enjoyed during a lengthy stroll along Málaga’s seafront promenade or the pint of Amstel that had been served with my paella the evening before.

The dishes presented to the other patrons of Café Bar Garden did not look particularly appealing but I went ahead and ordered a plate of spinach croquetas all the same, which turned out to be surprisingly filling. In the end, my bill came to €8. Taking into consideration that a single pint sets me back a minimum of €5 in my home town, I found this immensely pleasing. With my tummy already adequately filled, I decided to postpone my return to the tapas place Tío Triana had recommended until the following evening and called it a night.

“The Red One”

I rose early the next morning, eager to get the day underway. The skies over Granada had turned a lighter shade of grey and its streets were free of wet sand. I would spend a good five hours wandering around the Alhambra’s palaces and gardens, eyes big as saucers and mouth agape with amazement underneath my face mask.

I could go on and on about its splendour ˗ the superb views from the Alcazaba’s towers and ramparts, the tranquillity emanating from the large reflecting pool set in the marble pavement of the Court of the Myrtles, the ornately decorated gallery of the Court of the Lions, the outstanding stalactite work protruding from the dome of the Hall of the Two Sisters, the impeccably kept gardens of the Generalife ˗ but your time would be much better spent reading Washington Irving’s descriptions of the place. Even better still, if you ever get the chance to visit “The Red One” in person, I strongly encourage you to do so.

It was coming up to 3 p.m. when the rain set in for the first time that day and I was about ready for lunch. On my descent down the wooded slopes of the plateau, I paused in front of the statue of Washington Irving that was erected in 2009 to commemorate the 150th anniversary of his passing. The Alhambra is in much better shape than when he bade it farewell and this is partially due to his book’s popularity. For that, respect is due. Furthermore, through his colourful writings, I had come to regard the man as a type of travel companion and it was nice to have a vague image of what he had looked like.

Of Jarras and Tapas

On my way back to the hotel I stopped at a small taberna (tavern) and treated myself to two jarras of Lager Singular along with an equal number of tapas, a tortilla de patatas (Spanish omelette) and a mini-burger with fries. The bill amounted to €5. Somewhat perplexed, I double-checked the copy handed to me and saw that I had only been charged for the beers.

A flashback of the previous evening entered my mind – that look of confusion one of the charming waitresses at Café Bar Garden had given me when I did not order a tapa with my second jarra. So that’s how it works around here, I thought to myself. What a wonderful place!

Those of you that have been to Spain will surely know that it is commonplace to be served a small appetizer with your beverage of choice at bars and cafés. In my experience, however, these snacks usually consist of a bowl of chips and/or olives; a few slices of jamón or chorizoc at best. The granaínos have taken the whole concept of the tapa to another level. Though nicely saturated after my lunch at the taberna, I was already looking forward to dinner.

But first I would partake in yet another very sensible Spanish custom ˗ the siesta. Once awoken from my slumber, I called home. One of the first things my mother asked me was whether I had noticed anything of the huge Saharan dust storm that had swirled over the Iberian peninsula and large parts of France. The light bulb above my head started shining brightly. With that mystery solved, I made an attempt at removing the last residues of Saharan dust from my once immaculately white shoes and made my way down to El Peruano.

Another Round

Located a twenty-minute walk away from my hotel in a section of Granada that houses multiple university faculties and student accommodation blocks, I arrived just after 9 p.m. to find the place ram-packed. A couple were standing by the door and after a few expert hand gestures complimented with a few words of broken beyond repair Spanish, I knew enough to stand behind them and form a queue. By the time it was my turn to enter, close to 45 minutes later, the queue counted at least fifteen individuals and stretched around the corner. This was all very promising!

I started off by ordering a jarra and a portion of Peruvian chicken rice. The tapa, half a meal in itself, was delicious but the draught beer tasted foul so I switched to bottled Alhambra Lager Singular for round two. The accompanying dish of fried eggs and potatoes hit the spot as well. Last up was one more bottle of Lager Singular and a divine pincho (skewer), unquestionably the tastiest tapa I tried in Granada. For this minor feast of a meal, I was charged €9.50.

Comforted by the knowledge that there are still establishments that choose to operate in this manner in this day and age, when tapas are becoming increasingly synonymous with “sophisticated” cuisine, I slept like a baby that night.

Leaving Granada

Two nights and one full day after my arrival, I was off again. The next stop on my journey was Seville, a three hour bus ride to the west. “Tales of the Alhambra” begins with the author describing his overnight journey from Seville to Granada on horseback, now I was headed in the opposite direction. The skies were still cloudy but rays of sunlight were beginning to pierce the veil of mystery that had shrouded the city in the preceding days.

The urban landscape was barely behind us when the sun broke through, encouraging the Vega to sparkle. Seated in the penultimate row of the bus, I turned my head to the rear windscreen to check out the view and very nearly cried out in amazement. Off in the distance, to the east, I could see the Alhambra in all its glory, with the snow-capped peaks of the Sierra Nevada in the background.

In his book, Washington Irving also mentions the old Spanish custom of meeting expected guests along their route so that they may be accompanied during the final stretch of their journey and travelling alongside them for a while when they set out again. At that moment on that bus, I could not help but feel the Alhambra was sending me off.

Seville

The Cervezas Alhambra would continue to flow generously though, in Seville and then in Málaga. My first meal after leaving Granada was had at a restaurant whose name I do not care to recall, mainly because their entire staff was jittery to the point where I felt as if I was being rushed. It was one of those establishments hell-bent on being “sophisticated” and although the dishes I tried were tasty enough, the three jarras of Lager Singular and equal amount of tapas I had there cost me almost triple the price of my meal at El Peruano.

Fortunately, all the other places I dined at in the three nights and two full days I spent in Seville proved to be both more hospitable as well as affordable. Especially Triana Bar, situated in the barrio (neighbourhood) of Triana on the right bank of the River Guadalquivir, where I met Jorge and his 18-month-old toddler whilst waiting in line to be allocated a table out on the busy roadside terrace.

Our conversation was engaging from the get-go and when Jorge was notified that his table was ready, he suggested I join him. His wife would grace us with her presence not long after and the afternoon was spent indulging in the compulsory three jarras of Lager Singular and decadent amounts of food ˗ platters of fried calamari, deep-fried sardines, and jamón croquetas, just to name a few.

Málaga

The most satisfying culinary experience of the entire trip took place on my last night in Andalusia. I had caught a bus back down to Málaga that morning after spending two nights and one full day in Córdoba, the reason being that I was almost certain to miss my return flight had I chosen to cover the 160 km distance on the day of my departure.

Tourist season had by now well and truly gotten underway on the Costa del Sol and it took a while to find a hotel capable of accommodating me for the night. The one I checked into just happened to be situated a mere five-minute walk away from a restaurant that had been recommended to me by a lady I was corresponding with via an online dating platform who has since ghosted me, but that is neither here nor there. It would be far more constructive to mention that if you ever find yourself in Málaga, you should definitely check out Mesón Ibérico, and when you do, you had better show up early or make a reservation.

I showed up just after 8:15 p.m., some fifteen minutes before the place was due to open its doors for dinner. Five minutes later, a small crowd had gathered around me. By the time we were ushered inside by the doorman, the whole restaurant filled up instantly; every last seat in the house was taken.

The Last Supper

Perched at the far end of the bar, I kicked off the proceedings with a glass of locally produced vino dulce (sweet wine) and a helping of rosemary-infused cheese. After that came a total of four bottles of Alhambra Reserva 1925 and an equal amount of tapas, my undisputed favourite being the morcilla (blood sausage) from Burgos, which is incidentally also where Tío Triana hails from.

Halfway through the evening the newly available seat beside me was claimed by David from Madrid, in Málaga on business, who told me of one of the possible explanations regarding the origins of the tapas tradition and numerous other interesting anecdotes.

The story goes that, after recovering from an illness by drinking wine with small dishes between meals, king Alfonso X of Castile ordered that taverns would not be allowed to serve wine unless customers were also provided a small snack with their drink. Also known as el Sabio (the Wise), the involvement of Alfonso X would certainly make sense although some of the other explanations are equally plausible.

The Enchanted Ones

I myself spoke at length about the contents of “Tales of the Alhambra”, which I had finished reading in Córdoba. After leaving Granada, the tales had taken on a markedly mystical quality. In the second half of his book, my esteemed travelling companion narrates legends of Moorish princesses sequestered in one of the Alhambra’s towers by their own father, only to be whisked away by Christian princes on fleet steeds; of a Moorish prince capable of conversing with birds who enters a joust on a supernatural horse with the intention of winning the affections of a Christian princess, and of the treasures buried beneath “The Red One” in the depths of the plateau as well as the enchanted ones that guard them.

Like I told David from Madrid, I had also been enchanted. During my all too brief visit to Granada, I found myself surrounded by beauty that cannot be captured in a picture. The heavens opened and it rained sand. I ate well and drank plenty but the bill never exceeded €10. Not quite as incredible as the original tales, I know, but I can assure you my own experiences were nothing short of fantastic.

Leave a Reply